“WASHINGTON CITY PAPER”

It seems unlikely that Anastasia Tsvetaeva’s eyeglasses should have ended up in Rockville. Daughter of the founder of what came to be known as the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts and sister of famed Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, Anastasia spent 22 years jailed by the Soviet government. Her novel, Amor, which she smuggled out of prison, wasn’t published until she was in her 90s.

But here they are: the glasses that she wore while writing, along with a thin sheet of Amor’s manuscript and a pen she used to dedicate copies of her books, in the Washington Literary & Music Museum of the Five Russian Poets of the Silver Age. They were donated by the writer’s grandchildren and friends who maintain her archives, says curator Uli Zislin.

“When she was jailed, she was writing this novel about love,” he explains, through his translator, his granddaughter Julia Zislin. “She wrote it while being jailed, and page by page she...smuggled it out.” That was in the early days of World War II; remarkably, it would be another 50 years, Zislin says, before those pages would begin to appear in the literary magazine Moscow.

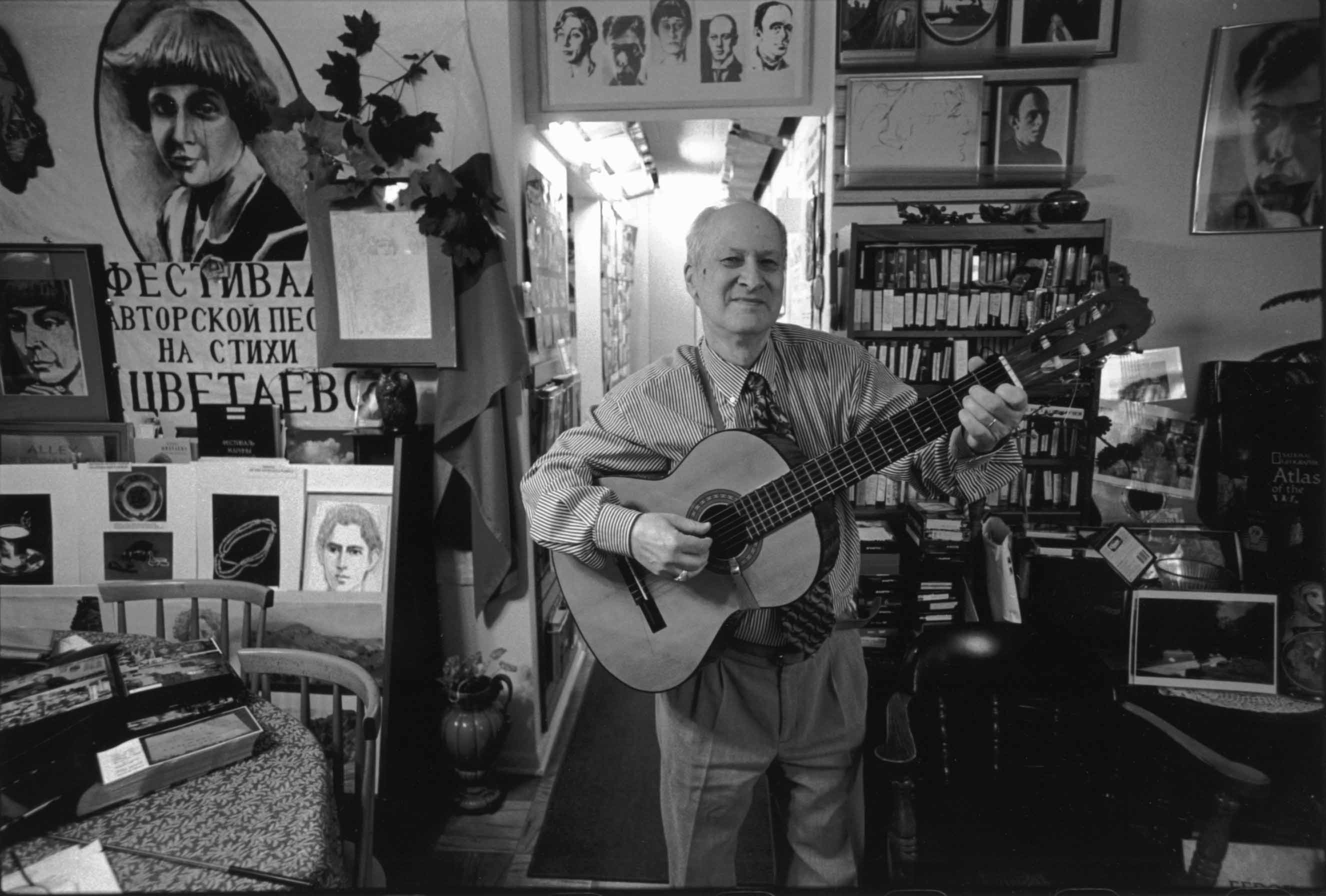

In the museum, however, the most remarkable thing about Tsvetaeva’s story might be the humble nature of its presentation: Her possessions are carefully laid out not in the sort of a climate-controlled, custom-designed display case one might see in any number of the buildings dotting the National Mall, but atop a set of cushions propped up on a small bed. The bed runs along one wall of a back room in Zislin’s apartment on Veirs Mill Road.

If you want to consult the multivolume set of reproductions of Tsvetaeva’s dedications—one of only three ever printed, according to Zislin—turn around to the row of bookcases that cuts the modest space in two. The adjacent hallway is lined with pictures and posters, including notices for concerts that Zislin has presented in Boston, Jerusalem, and Moscow. The walls of the living room are similarly covered; one features a row of portraits of the museum’s five titular poets: Anna Akhmatova, Nikolay Gumilyov, Osip Mandelstam, Boris Pasternak, and Tsvetaeva’s famous sister, Marina.

“It was really very shocking,” recalls Natalia Romanova, a lecturer in Russian at the University of Maryland in College Park, who brought about a dozen of her students to the apartment-cum-museum last fall. “We were walking along the corridor looking at different posters and photographs, and then, oh, all of a sudden, there’s a kitchen.”

More surprising, though, was the museum’s chief asset: its unflagging tour guide. “[Zislin] was on his feet for two-and-a-half hours, singing, talking, showing us around,” Romanova recalls. “I was amazed.”

Although Zislin describes himself as Russian Poets’ curator, his job differs somewhat from traditional museum work. There’s the singing, for starters: performances of Zislin’s own musical arrangements of works by a whole host of Russian poets, including himself. And the fact that Zislin bought many of the several thousand items on display with his own money—or that scholars using the museum’s archives sometimes stay with Zislin and his wife as overnight guests.

“Some of these people couldn’t sleep because they found so much information,” he says proudly. “They just kept on reading.”

Though Doctor Zhivago scribe Pasternak may be the Silver Age name most familiar to Americans, Zislin confesses a special affection for Marina Tsvetaeva. A corner of the room dedicated primarily to her includes photographs of her favorite jewelry and clothing, and the museum organizes a bonfire each year on the eve of her birthday.

Zislin, 75, was born in Moscow, he says, “by some miracle very close to the house where Marina Tsvetaeva was born”—only about 300 meters away, he estimates. It’s an area famous for Pushkin Square, named for one of the fathers of modern Russian literature, and one that Tsvetaeva wrote about in her poems.

Zislin began writing music as a university student and started writing poetry after graduation. A physicist by profession, he established a music and poetry club in his spare time. Candle, as it was called, began meeting in 1979, sometimes presenting music by young composers, sometimes featuring the works of prohibited poets. Writers of the Silver Age—roughly 1890 to 1925, following the 19th-century Golden Age triggered by Pushkin—were popular choices.

It’s hard to generalize about the degree to which Silver Age poetry was accepted under the Soviet regime. Gumilev, Zislin notes, was banned outright, while Pasternak was published occasionally. In any case, the poets themselves often suffered: Gumilev was executed in 1921, and 17 years later Mandelstam died in the Gulag.

Akhmatova, whose early verses made her a sensation in prerevolutionary St. Petersburg, later saw her poetry unofficially banned for nearly 20 years. In the back room of his museum, Zislin displays a hunk of birch tree symbolic of the one used by an Akhmatova fan imprisoned in the late ’30s. She peeled the bark away from the tree and from memory carved some of Akhmatova’s poems into the sheets. Later, she bound these together with rope and sneaked the rudimentary book out of prison.

“Thirty years later, this book was found, and it was gifted to Akhmatova,” Zislin explains. “She valued it very deeply, and she would even at times say she valued it more than a Nobel Prize, because it shows how much people loved her.”

Zislin began gathering such materials—and thinking about the possibility of opening a museum—in 1978. By the time he and his wife moved to the United States, in 1996, he’d collected about 400 items—mostly books, newspaper and magazine articles, and other archival material.

“We came to our children,” he says, noting that his daughter had moved to the United States in March 1995 and that his son emigrated about a month after he and his wife did. The collection followed Zislin here, by sea. “One ton of freight,” he recalls, speaking through a friend, Dana Yanovich.

“Only a circle of specialists knew about the work of these people,” says Julia, translating for her grandfather. “And even they didn’t know everything. So he views this as his obligation to both the poets of this era and to the people who couldn’t enjoy it at the time...to remember the poets.”

The museum, which has been operating officially since 1997, represents just one outlet Zislin has for that aim. In April 2003, with the aid of Russia House and the Friends of the Guy Mason Recreation Center, he broke ground on the Alley of Russian Poets, located in D.C.’s Glover Park neighborhood. The alley began as a row of five trees, one dedicated to each of the museum’s five

Silver Age poets. Another five were planted a year later to commemorate Aleksandr Pushkin and his contemporaries. Ultimately, Zislin says, he’d like to add a monument to Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and other Russian composers.

As the self-described “only curator of a museum who sings to his visitors,” Zislin has also become something of a regular on Literaturnyi Razgovor, a program broadcast through the Russian Television Network of America. Since 1999, he’s made 10 appearances, all resulting from a letter he sent to the show’s host suggesting that he be allowed to perform a few of his songs on the air.

Scores of other performances can be found on the museum’s Web site, where they’re divided into “Songs about women by Russian Poets” and “Songs about world towns by Russian poets.” The later category even includes a few works of Zislin’s own, among them “Songs of American Muscovites.”

He begins one museum tour with a song adapted from a work by early-20th-century Russian poet Sergei Esenin. Strumming an acoustic guitar, Zislin sings first in Russian, then in English:

Just below my window

Stands a birch tree white

Under snow in winter

Gleaming silver bright.

When hosting Americans, he always starts with a song about snow, he says, because “in Russia, winter is much more lengthy than here, so it’s much more significant.”

Zislin’s drive to spread Russian literature often takes him well beyond the walls of his museum—and not just for a high-profile concert or two. Gayl Gutman, co-chair of the Friends of the Rockville Public Library, recalls the day he popped up at one of the group’s regular public meetings about a year ago. Zislin waited through nearly the entire meeting before taking a turn to speak—and when he did, it turned out that he’d been studying the plans for a proposed new library.

“And he basically said, ‘I’ve seen this library before,’” Gutman recalls. “‘I see you don’t have much space, so I never ask. But now you’re building a large library—can we put some Russian books there?’”

The Russian Book Initiative began meeting the next month.

Zislin hasn’t always found it so easy to enlist folks in his cause. Over the years, people have donated an eclectic array of materials to the museum: a portrait of Akhmatova given by a Chicago-based artist who Zislin says was the last to draw her; the marble used to create markers at the Alley of Russian Poets; an almanac from Israel that includes an article on Marina Tsvetaeva. But monetary donations have been much harder to come by.

“I am already 75 years old,” Zislin says, “so I would love to have an actual space for this museum.” Nothing fancy—just a place to house the materials. “The main point is...to make this accessible to more people, to have it in a location that’s accessible to people.”

To this end, the museum’s Web site shows various items and projects donors could fund, ranging from the “purchase [of] stands and equipment” all the way up to increased advertising. Expansion of the exhibition space is listed twice, though, Zislin says, “nobody ever replied to this.”

Producing a notebook, he shows how much of his own money he’s spent just adding books to the collection—so far, about $6,000 on some 628 volumes. And that’s just since 1999, when he began keeping records. “When he has even small resources of money, he buys something and does something to keep the museum going,” translates Yanovich.

He envisions a gradual move to a new space—perhaps beginning with a single exhibition, with the other materials following later. “I’d love to dedicate my last years of life to that,” Zislin says, again through Julia.

For now, at least, the material donations continue. Early in the tour, Zislin shows off a bronze medal commemorating the 1899 centennial of Pushkin’s birth. Nearby is a newer piece, one actually donated by a Pushkin—the famous poet’s great-great-great-grandson Aleksandr, himself a poet, who once saw the curator give a concert in New York.

“Very good man,” Zislin says in English, “very good poet.” In Russian, he adds,

“He visited this museum not so long ago.” Pushkin’s gift, presented last fall, was a poem:

I’m impressed by the passion of Uli

Only one thought bothers me

All around is museum and museum

Where does its owner live?